Lloyd Maines: Producer / Musician

Courtesy photo

From the Texas Governor’s Office on Music (Texas Music Office)

| Prolific producer Lloyd Maines has worked on 4,000-plus projects in his career, including producing tracks for his daughter Natalie Maines’ band, Dixie Chicks, and their multi-platinum selling albums.

One of the first things you’ll discover about producer, pedal steel player, Grammy Award-winning musician Lloyd Maines is that he’s incredibly humble considering his exceptional career…down to Earth in that earnest, hardscrabble West Texas way that the thousands of musicians and music industry veterans that have worked with him can attest. The man lives and breathes music, and as one of the most sought after producers in Texas, headed into his fifth decade as a music business professional, he shows no signs of slowing down. |

Pop a top, fire up our Lloyd Maines retrospective playlist (he’s producer and/or pedal steel player on every track), and join us as we dive into part 1 of a 2 part interview where Maines takes us through how he and his brothers learned to play music, how The Clash got turned on to the Joe Ely Band, the eureka moment Maines had while producing Terry Allen’s seminal “Lubbock (on everything),” and how Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Live at Gruene Hall” gave birth to an entire sub-genre of Texas country music.

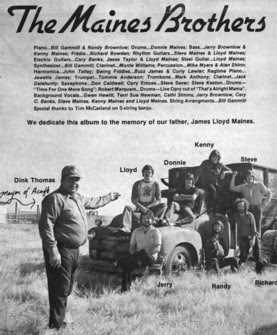

TMO: Early on as a teenager, you started playing music with your brothers as the second generation Maines Brothers Band. Did you ever study music as a kid, learning how to read music and all that? How’d you pick it up? Maines: “I’ve never taken a music course at all. Never learned to read music at all. I kinda picked it up from watching my father (James Maines) and my uncle (Wayne Maines). They had a weekend band (the first generation of the Maines Brothers Band) back in West Texas when I was growing up. And my brothers and I would sit around the living room floor and watch them play and just soak it up as best we could. And we were only in the fourth, fifth, and/or sixth grade. “And then when I was in the 8th grade, I remember I had my parents buy me a Mel Bay Chord Book. One of those $2 Mel Bay instructional books, where it just taught basic chords. You know, nothing fancy. It showed a picture of a guy’s left hand making chord patterns. So I would just copy those. And that’s the way I learned my chords. And I practiced on my dad’s old…my dad had an old 1958 Gibson acoustic guitar. So I practiced on that and learned the chords, and then I taught the chords to my brothers. I have 2 brothers (Steve and Kenny) just younger than me. And my other brother (Donnie) came along later. I taught them the chords, and then one brother (Kenny), we worked on bass for him, and that’s how we started our young Maines Brothers band (by 1967, known as the Little Maines Brothers Band). |

“We just learned as we went. We learned by listening to Merle Haggard records, Ray Price, Johnny Bush, Buck Owens, George Jones. We knew all those songs by all those artists. We just learned (via) on the job training. We started playing gigs when I was 14 years old. My brothers were 12 and 11. The 11-year-old (Kenny Maines) played bass. And the 12-year-old (Steve Maines) played acoustic and sang. And then when I was 14, I got an electric guitar. And I tried to play electric…and we gigged all around West Texas: VFW halls, rodeo dances. We were too young to play in the bars at that point, (though) we still started playing when we were underage in some bars. My dad would go with us, and he was the chaperone that was ‘of age.’ So we started off early and just learned (via) trial by fire.” TMO: And you’re going by the Maines Brothers Band at that point…playing covers, and different places around Lubbock. And at some point, you guys split up to go to college? Maines: “We did. We played all through high school. I got married right out of high school to my high school sweetheart, and we’ve been married almost 47 years now.” TMO: Congratulations! That’s amazing. Maines: “Thanks…yeah. So I got married right out of high school. One brother (bassist Kenny Maines) graduated and got a gig in Las Vegas playing for this guy, Kenny Burnham. And then my other brother Steve went to Texas Tech. And actually he even went to Texas State for a while, I think. And then went back to Texas Tech and graduated. And then my youngest brother who came along a little later, he was our drummer. And he didn’t start drumming full-time with the Maines Brothers until the late ‘70s, once he got out of high school. He graduated in ’76. “So once everybody got out of high school (and went separate ways), I started playing with Joe Ely at that time. And also working in a studio in Lubbock called Caldwell Studios. And that’s actually where I started working on my studio chops. Man, I had no training in that either. I just learned it as I went.” TMO: And did you have a mentor there at Caldwell Studios? Maines: “No…not really. The owner was a good musician and a good engineer. His name was Don Caldwell. We just figured it out as we went. By that time, I had started playing pedal steel, and was doing session work on pedal steel, and I really enjoyed it. And (learning in the studio) just kind of evolved. Back in the early ‘70s. I was recording and playing on everything I could get my hands on: hardcore country, heavy metal rock ‘n’ roll. I even played and recorded Conjunto music…and Tejano stuff that would come through the studio where sometimes they’d want me to play or produce. And I’d just dive right in, man. I learned it…and soaked it up early. “And then I started playing with Joe Ely in 1973. He wanted to put a band together and just do a couple of weekend dates to try to get enough money for him to relocated to Austin.” TMO: Was Ely familiar with you from your band with your brothers? Or did y’all cross paths at the studio in Lubbock? |

Maines: “Well, it was both. Back when the Flatlanders first started, we used to cross paths. They used to come out to see us play. We’d go hear them play. So we knew of each other, but had never really worked with each other in the studio. Joe was a great harmonica player. So anytime we needed any kind of harmonica player in the studio, we’d always call Joe. And he’d run down and lay a part down. So that was really how I got acquainted with him was (working) in the studio…and just kind of passing by each other (in Lubbock). But, he asked me to do these 2 weekend dates with him as he was trying to raise enough money to move to Austin. And man, we did these 2 throw-together band dates. We didn’t even have a drummer. It was just me on steel, Joe on guitar, a bass player, and a guy who played an electric fiddle. And man, the response was so absolutely unbelievable. I’d never experienced that. Joe was doing some original stuff. He was doing some Flatlanders stuff. He was doing some Hank Williams, some Jimmie Rodgers. And man, the crowd went absolutely wild over what Joe was doing.

“So that’s when he decided to not move to Austin, at that point. He stayed around (Lubbock) and started his Joe Ely Band days.

“We did some demos. And Joe got a deal with MCA Records. And I wound up doing most all of the records with him. I think he did about 8 or 9 records for MCA.”

TMO: Yeah, I’ve heard most of that stuff. And it holds up so well!

Maines: “Oh, yeah!”

TMO: I’ve always been curious how the guys from The Clash…if they came to Joe’s music through liking Buddy Holly, and then started digging deeper? How in the world did those guys in London get hip to the Lubbock music scene?

Maines: “Well, I was there in San Francisco around the first time (the Joe Ely Band and The Clash met). I think Joe had talked to them before. But we were in San Francisco, and I can’t remember if Joe was doing an in-store for one of his records, or if The Clash were doing one of their in-stores. But I know that we were in the same record store at the same time. That’s all I remember. And that’s when Joe Strummer told his manager that he wanted the Joe Ely Band to open for some of their shows. That was the connection.

“I just think that Strummer was a huge fan of Joe’s music and his whole approach. And they loved using the steel guitar as a rock ‘n’ roll instrument. Strummer was just all about that.

“I think we did about 6 shows in Great Britain. Then probably about 6-8 shows throughout the United States opening for The Clash.”

Lloyd Maines and Terri Hendrix — Photo by Mary Jane Farmer

TMO: Was the reception pretty good? Was it similar to what Joe would receive on his own?

Maines: “Well, you know, it was pretty strange. I would say the reception was good, but…I’m not sure how old you are…you sound pretty young…?”

TMO: I’m mid 40s.

Maines: “OK…so you were around back then, but I tell you, man, the whole punk/new wave movement…the crowds were so over-the-top ridiculous.

“That was back during the days where if they threw stuff at you, they liked you. It was just nuts! I would say the reception was good…but it was just different, because, man, these punk kids were trying to react how they thought they were supposed to react to punk music. And you know, I don’t even consider The Clash punk. Those guys were serious players. They were not just thrashing. They had great songs. So it was kind of a new wave (rock) thing. But their crowd in England was totally receptive to Joe’s stuff. And over there, the British crowd that knew how to react to the music of The Clash, they didn’t throw much of anything at all. It was just like a huge party. And they’d throw cups. And they’d throw ice. Kinda like these crowds do now where they shake up a beer, and let the beer spew all over the crowd. In England it was fine…harmless stuff.

But as usual, we came over here, and the American crowds were trying to emulate how they thought they were supposed to react. And sometimes it got dangerous.

“We played the Hollywood Palladium, and there was about 5,000 people there. And the crowd was throwing bottles. They were throwing cans. And at one point, Joe Strummer walked out and he said, ‘If you don’t stop this now, there will be no music.’ He was totally jacking their jaws. And they finally stopped. And The Clash went ahead and played, but it was a melee. You know, people thought they knew how to act, but they didn’t.

TMO: That is crazy. I know folks are gonna be curious about your producing credits too. You’ve worked on so much stuff.

Maines: “Oh, yeah…”

TMO: And so many interesting periods of stuff too: from the Lost Gonzo Band stuff, to all the different Jerry Jeff Walker stuff…and I was reading that you said a lot of the newer country folks – folks that have really strong careers now – like Pat Green and some of those guys, that they kind of came to you from being familiar with your production work for Jerry Jeff Walker. Is that correct?

Maines: “Yeah. I think so, yeah. Let me even go back further than that. My first (work as a producer), what I consider my coming into my own as far as helping produce a record, was the Terry Allen ‘Lubbock (on everything)’ in 1977. And I don’t know if you’ve heard that record, but it’s become an iconic record. In fact we did a tribute to it with Terry Allen and a lot of the original members in Lubbock just about a year ago exactly at Texas Tech. And then we did another (tribute reunion show) here at that Paramount about 2 weeks ago.”

TMO: Yes! I – and many people I know – couldn’t even get into that show at the Paramount. (I think every musician in central Texas was there.)

Maines: “It was a phenomenal, unbelievable show. I mean, I’ve never played a show where there were that many spontaneous standing ovations. I counted seven; my wife said there was more than that. She was in the audience.

“There were standing ovations after songs, instead of at the end of the night. Just an amazing deal!

“…so…even though I had done a couple of records with Joe Ely at that point, a couple of the MCA records, which were a great experience. And I didn’t produce those. They were produced by a guy named Chip Young. So this Terry Allen thing was the first one that I was able to get my hands on and participate in the production.

“And once I did that, I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life: record music…and play live too. I’ve always continued to play live. But producing is really where my passion was laying. So that went all the way through the ‘80s, and I produced tons of stuff in the ‘80s. Mainly local West Texas people.

“Jerry Jeff had taken a couple of years off. And was just playing solo. He was getting his health together and jogging and doing all that stuff. And he called me up one day and said, ‘Man, I’m gonna do a record live at Gruene Hall. I enjoy Gruene Hall. I like it down there!’ This was 1988. And he said, ‘I just wanna put together guys that I wanna work with. Even if it’s not really a band, I just want to put together a recording band.’ So he got me, and a guy named Paul Pearcy on drums. A guy named Roland Denny on bass. Champ Hood on guitar and fiddle. And a piano player out of Dallas, a guy named Brian Piper.

“And he just brought us down and we rehearsed one day out at Jerry Jeff’s house. Actually I take that back, we rehearsed one day at his house, and we did some gig in Dallas. And then went straight to Gruene Hall and recorded ‘Live at Gruene Hall.’ And it pretty much helped kick-start Gruene Hall’s career. Up to that point, they were still just kind of a weekend dance hall. Once Jerry Jeff did that “Live at Gruene Hall,” man, it became such a popular record, and really kicked-off what you see there now…which is this over-the-top tourist thing.”

TMO: …going back to Terry Allen’s ‘Lubbock (on everything)’ and it being where you truly discovered your love of producing. It’s interesting that now it’s gained this cult following. And, of course, I wasn’t around back then to witness it. But it seems like not many people actually heard the record back then. Is that true? Obviously, musicians heard it and loved it…

Maines: “Right, right. It was mainly an art community record (with just a few hundred copies originally pressed). Terry’s a great visual artist too. But people like the band Little Feet knew of Terry because they recorded his song ‘New Delhi Freight Train.’ People like Bobby Bare. Bobby Bare cut one of the first recordings of ‘Amarillo Highway.’

“Boy, it’d be great…I’d love to lay my hands on a version of that. I’m sure it’s floating around out there somewhere.”

TMO: It’s gotta be out in the world somewhere.

Maines: “Yeah, yeah. But for that ‘Lubbock (on everything)’ record…in 1979, when Rolling Stone was doing their year-end wrap-up. They actually picked that record as one of the most important record of the ‘70s.”

TMO: Wow…ok. Ok.

Maines: “And then, here it is 40 years later, and it’s actually got stronger legs than it did back then.

“I feel great for Terry Allen, because he’s a monster, monster writer. His writing is on another level…like, on another dimension! So it’s great that this record has been re-released, re-packaged. And in fact, Rolling Stone did a review of it and said they stand by what they said 40 years ago, and they still think it’s one of the most important records ever.”

TMO: That was so early on in your production career (1977). Do you approach projects the same these days? Or does it depend on if you’re doing pre-production…or…?

Maines: “It depends. I approach every project differently. Every project has its own scheme that it needs. And I just kind of let the songs in the project dictate how I handle it.

“There are only 3 hard rules when I produce a record. And everything else, I just go with the flow. My three hard rules are: ‘In time, in tune, and under budget.’ (laughs) And that always works pretty well.”

TMO: (laughs) Those are all important.

Category: *- Features